Resources

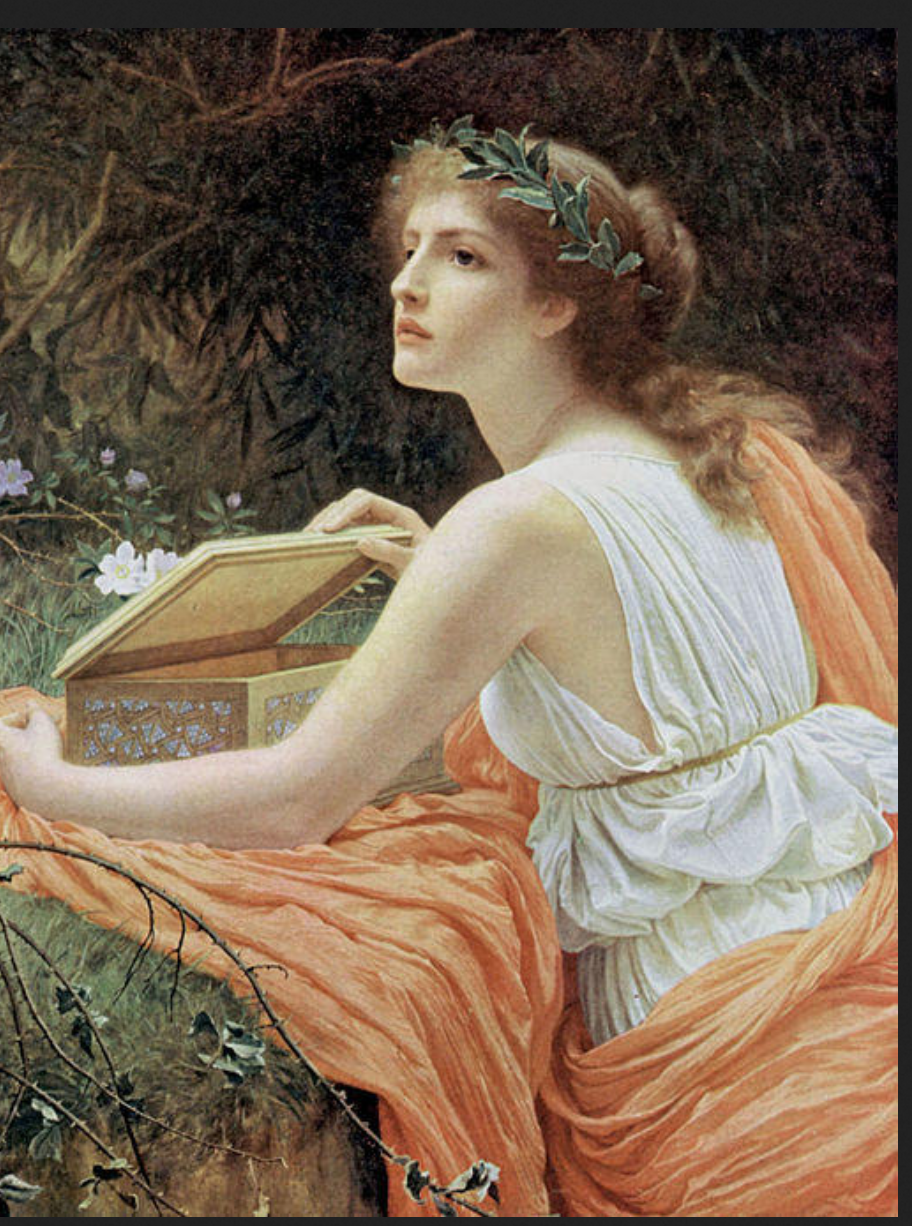

The resources listed below are concerned with interlocking issues involving self-identify, self-efficacy, and self-confidence. In general, in so far as every good question’s answer prompts a further question, every problem’s solution leads to a further problem, and the very act of questioning established orthodoxy is much like opening Pandora’s box; or more colloquially “Opening a can of worms”. But of course, if you want to catch those fish, you’ll need to open that can!

In the philosophy of science literature this approach has been labelled Progressive Problem Shifting by Imre Lakatos/p>

Left handed children: Dr. Johanna Barbara Sattler

FOREWORD of The Left-Handed Child in Elementary School by Dr. Johanna Barbara Sattler; pub.Auer Verlag, Donauwörth, 1993

Director of the Department of Primary and Secondary Education in the State of Bavaria

Until recently, primarily elementary school teachers were being confronted with a phenomenon for which there was no explanation. There were children coming from kindergarten, who appeared to be of normal intelligence, enthusiastic, and active. Once in school, however, these children suddenly began to change. By the time they reached the first grade, they had already started to fall behind. On the outside, they appeared to be somewhat aggressive and timid. Learning ceased to be a joy for them. Since this phenomenon did not just involve an isolated minority, teachers began to search for an explanation. For a time, it was assumed that the causes for this change might lie in the families of the children; the atmosphere of the classroom; or even in the teachers themselves. These early attempts at finding an explanation were mostly without success. Who would have guessed, however, that the roots of this problem could actually lie in the conversion of inborn handedness?

In 1987, the State Institute for Pedagogy and Educational Research for the School Advisory Center in Germany compiled materials on “The Left-Handed Child Starts Elementary School”. At the request of the Bavarian Ministry for Education, Culture, Science, and Art, this material was then expanded and addended in 1989 to become Suggestions for the Reception of the Child Into School.

Scientific journals and media reports then repeated the information to be found in these materials adding new dimensions to the issues to be discussed. Soon, it became more and more clear that a problem had been hit upon which was of the utmost importance for all those affected. Moreover, it became increasingly evident that it was impossible to be against the conversion of handedness without modifying, learning and work conditions for left-handers. Thus, in order to truly help left-handers and stop them from being disadvantaged members of our society, the real-life barriers facing this group had to be torn down step by step. This new work represents the first, comprehensive, user-friendly guide for teachers and educators. It has been specifically designed for these professionals, as they are often the first ones to come into contact with children of the age-group most vulnerable to this issue. We hope that the information provided here will be quickly and efficiently distributed.

Dr. Peter Igl

The Knot in the Brain: Dr Johanna Barbara Sattler

The Knot in the Brain: Converted Left Handedness: Dr. Johanna Barbara Sattler; pub.Auer Verlag, Donauwörth,

A very personal introductory note: How spme individual destinies led to a personal nsight.

My friend Karl was always the best in grammar school. He also had a big heart and was good at sports. He was liked by everyone. All readily felt that he would go far. Thus, no-one was envious of him when he started studying medicine at university and then majored in surgery. Everyone knew that, thanks to his sharp memory, he would be able to master other subjects just as easily as he had once, on account of a bet, been able to learn five languages.

The proof of his all-round talent was already evident in his youth. One summer he dated the daughter of a watchmaker and worked with the father. Karl managed to absorb so much knowledge that at the end of the summer he was able to increase his pocket money. He did so by repairing and refurbishing watches and by buying up cheap bric-a-brac items which he then transformed into genuine, working antiques. All this seemed to prove that Karl was clearly destined to master the intricacies of surgery. And, true to form, he quickly made good on that promise. His assistant position at the university came then as no great surprise.

I met Karl some years later while holidaying in Spain. I was confused as to why he was there in the middle of the summer semester. He told me he had had some bad luck. The chief surgeon of the university hospital, who was well-known, had travelled to a conference unexpectedly and Karl had filled in for him. A tendon in his right hand had been injured when he was handed a surgical instrument while engaged in a somewhat difficult operation.

The story of his injury sounded like a comic anecdote. The chief surgeon was left-handed, to which his whole team had adapted accordingly. Karl, however, was right-handed. In addition the tension during the operation didn’t help matters much either. Suddenly, a routine manoeuvre turned out to be the wrong one for Karl, resulting in his injury. Karl was unable to operate with his left hand and therefore unable to fit seamlessly within that team. He had no option but to take time off.

Yet again I had the opportunity to admire his will-power and self-determination when I learned he used his absence to hone his left-handed skills. With impressive determination, he practiced virtually all day and extended it to writing only with his left hand. He had even got hold of several textbooks that dealt with exercising the left hand. He was fully committed to increasing the precision and adeptness of his left hand so that in future he would be able to operate using either hand. In short, he thought, by the end of his self-training, he would have two right hands.

When I met Karl some time later, he was still laughing at the shock he had felt on first trying to use his left hand to perform complicated tasks. The result had been disastrous. I myself have tried to do the same and noticed that my left hand is practically useless when used as the main hand. I wasn’t as ambitious as Karl, so I left it at that and there was a lengthy gap before we saw each other again.

About eight years later I tried to have a patient referred to a suitable spa. I was unsuccessful because, unfortunately, it had no spaces left. During my phone call, I was suddenly aware that the director of the spa was Karl. He must have suffered a tremendous loss in professional standing to occupy such a position. My own professional curiosity was raised to such a degree by something in his voice that I decided to personally accompany my patient to the spa. The undertone to Karl’s voice had set off all sorts of alarm bells in me.

When we met, sat and talked together Karl exuded resignation. He expressed fear about having a mysterious, progressively degenerative brain disorder which had apparently taken on psycho-pathological dimensions. In spite of this fact, Karl tried to gloss over everything, forcing himself to be optimistic. At least, he felt, he was earning a lot of money in his current role and was left in peace.

He then recounted to me how, on his return from Spain, he had studied neurology intensively as he wanted to specialize in neurosurgery. He began preparing for his post-doctoral research even more intensively. And this was when, Karl, for the first time in his life, had to realize that he somehow couldn’t keep up. He likened himself to a motor that cut out several times at full throttle. His memory began to fail him and then, because of the stress he experienced as a result of remembering these ever increasing lapses of memory, a psychological “circulus vitiosus” was created. Then, his hands began to shake and consequently he was no longer able to execute precise movements. His time as a surgeon was over.

His whole world fell apart. Everything that he had doggedly worked for since childhood was ruined. It was only a lucky act of fate that saved him one night from carrying out a carefully planned suicide.

Karl had explored a host of differing diagnoses, from “endogenous psychosis” via multiple sclerosis to Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, all without positive result. He took to drink and got into trouble with the dean of his college. Then his troubles started with his wife. He appeared to solve some problems through the help of his father who got him his current post as spa director. After his subsequent divorce, Karl was not yet willing to enter a new relationship. As he himself said, he suffered from hypochondria and fearful anxiety about the future. I was only too able to confirm this accurate self-diagnosis and gave him some routine psychological advice for his future. I left Karl with a nagging feeling of powerlessness because I, too, had no explanation for his problems. Karl remained a portent of unfathomable fate, one which I tried to ignore.

Later still, after I was already looking back over a long, quite successful psychotherapeutic practice, an important ministerial civil servant was recommended to attend my office. He had already tried five therapies which he had discontinued as well as two failed suicide attempts behind him. Before him lay the prospect of the sudden termination of his career, either by being posted into a dead-end position or forced into early retirement. He described his fate to me with considerable resignation. He said it had all started with his being embroiled in a car accident. He was innocent but a child had been killed. Then, depression hit….

His wife subsequently left him, taking the three children. Then, due to faulty advice, he lost all his savings because the investment company where he had placed his savings became bankrupt. Returning home from a visit abroad, he found his house had not only been burgled but burnt out. And he was deemed to have been under-insured.

Later, delivering a routine lecture before a European Community Committee, he suddenly lost his train of thought. His memory had failed him. He began stuttering and stammering so finally left the lecture hall in a sudden panic. After that, his panic attacks came with frightening regularity. He even managed to forget what to say in relatively routine meetings and so was forced to read everything from notes. This did not always work well, especially when he had to answer unscripted questions.

During his consultation my memories of Karl and his lapses of memory were suddenly revived. After the patient himself described how he became increasingly like a “Zombie”, he had been tested for psychosis, multiple sclerosis, and Alzheimer’s – just like Karl and again without any positive results. I considered everything that was available to the neurologist, psychiatrist, and the psychotherapist by way of diagnosis. We even explored his memories back to his earliest childhood for a cause; all to no avail.

On one occasion, the patient looked at a poster on a wall announcing the latest exhibition on Leonardo da Vinci. I noticed how the mirror writing reproduced on the poster absolutely fascinated him. I told him that this highly gifted scientist and artist had written all his records using mirror writing. Apparently, he had done this in order to guard against it being recognizable to all but some. My patient said, amused, that he, too, could write backwards. I suddenly remembered a presentation by a colleague who had also mentioned that mirror writing was one of the abilities that both left-handers and persons who have been converted demonstrate. My patient, however, flatly denied ever having been left-handed. I did not abandon the possibility of him being left handed so I took him to Dr. Sattler with her computer tests. They had once revealed me to be hopelessly right-handed. The opposite happened to this patient. He tested as a true left-hander who had been converted to his right hand. Only then did he remember that formerly he had used his left hand far more for executing various tasks, especially for work requiring precision and strength. Even in kindergarten, he had started writing with his left hand but he had been “cured” of that quickly and successfully.

It was then that I began to study Dr. Sattler’s work intensively and, at the same time, made contact with numerous other psychotherapists. We looked for patients with similar symptoms who had had little or no success with varying therapeutic interventions. We entered their biographical data into the diagnostic computer programme to ascertain their handedness. To our great amazement, nearly all the patients had once been left-handers who had later been converted. Two patients had even been converted to their left hands after having suffered accidents to their right.

And suddenly I saw before me a foreign, alien, individualistic and lonely world where people who have been converted from left to right, live and have to exist with consequences that I found hard to understand. All were in the final stages of their suffering.

Now the reason for the tragedies in Karl’s life finally had an explanation. His Herculean training amounted to an attempt to convert himself to being left-handed. Karl was unwittingly confronted with the same set of consequences as one who had been converted as a child. These effects, which are difficult enough for any “normal” child to deal with who been converted, are intensified for adults. Like many childhood maladies, it seems all the harder to cope with as an adult.

The case of the ministerial civil servant was somewhat different from Karl’s; nevertheless the causal mechanism was completely clear. His car accident and its dire consequences played a crucial role in his subsequent psychological destiny. The additional strenuous effort he had invested his whole life into constructing mnemonics in order to ensure he achieved commensurate with his intelligence was dissipated in an instant. The entire additional reserve of energy which went towards carrying the exhausting emotional baggage was suddenly lost.

It is only with continual, increased concentration that a converted left-handed child can summon the additional energy that is needed to survive. It is precisely this energy, however, which is continually drained through the emotional burden of the original trauma. It is missing when needed to think clearly, use one’s memory, and solve complicated problems: the converted left-hander’s mind simply gives way. The same ‘law’ which applies to loss of sleep and of virility applies here as well. Ultimately, the memory of having had one mental breakdown is enough to induce another, and another and another.

At the time of writing, I am now familiar with hundreds of similar examples. My colleagues have also been confronted with similar cases. Surely this reflects only a fraction of the total of human misery. I say only a fraction because only a minority of survivors actually try to seek help in the form of psychotherapy.

In our practice, we have come to acknowledge the potentially serious consequences the phenomena of converted handedness can have for those in our society seeking equal opportunities within the selection processes of our performance-driven culture. In societies where advancement is dictated by successful performance during written examinations, the possibilities for future attainment are restricted. This happens from childhood onward. Astoundingly, no one noticed what was going on until a solitary scientist began talking about and presenting her intensive research.

For me, the research of Dr. Sattler has increasingly proven to be a milestone. From my perspective as a psychotherapist who has been in ‘the business’ for many years now, Dr. Sattler’s work will one day be widely acknowledged for having identified one of the most important factors that defines personal existence. Her work, undoubtedly in my opinion, constitutes one of the most important bodies of scientific research of this century. My fascination with her practical research derives especially from the relationship between theory and practice. This connection continues through her current research.

The insight that one gains when confronting the true-to-life research of Dr. Sattler and her research team is simply stunning. Whereas previously hundreds of complicated theories had run rampant, there now stands a clear, single, concise, commonsensical, easily understandable simple Cause-and-Effect ‘theory’. This leaves me puzzling why we never noticed the connection before. Why had no one been able to put the ‘obvious’ pieces of cause-effect, and action-reaction together before?

Dr. Sattler’s success is all the more astounding given the many different branches of science that had attacked this problem. Sometimes they had even come very close to finding the solution. But no one before Dr Sattler was able to place the individual pieces together to form a complete picture with all its true dimensions. This is, of course, the case with any great scientific discovery.

In 1987, this discovery was deservedly honoured by the International Neurophysiological Conference in Istanbul. Here, as a German scientist, Dr. Sattler, was invited to present her work personally… in English! After her presentation, Dr. Sattler and her work were referred to the world over. She continues to make countless radio and television appearances. Her portfolio of press announcements alone is, at the time of writing, over three and a half centimetres thick.

Finally, it occurs to me that we are dealing here with a classic example where many personal problems can be completely eradicated through simple preventative measures. At the same time, we also have an extraordinary straightforward example of a cost-and-benefit analysis. The earlier the intervention is introduced, the more successful and the more cost-effective it will be. This surely means we must start in kindergarten and primary schools. The case for such early prevention is exactly the thrust of Dr. Sattler’s work which is presented here with the greatest of clarity.

Dr. Ivo-Kurt Cizek, Dipl.-Psych., M.A. (Soz.)

Trauma and latent talent! Maurice Blik

Igniting the spark, THE TIMES Friday 30 September 2005 (Times 2) Interview by Richard Morrison

The story of Maurice Blik gives hope to anyone drifting into middle age. In his 40s, he changed his life

completely and is now one of the world’s top sculptors.

How late can you change your life? If you are in a comfortable rut with a job that doesn’t stretch you but pays the bills, is it time to shrug and accept the way things have turned out? Even if you have a feeling that you could have made more of yourself? Even if you sense that within you, flickering still, is a spark of creativity that might have lit up the world? Two decades ago, Maurice Blik had more cause than most to take the easy path through the rest of his life. His childhood had been wracked by horrors worse than most of us could imagine. It had left him physically and emotionally scarred. He had known what it was like to be a dispossessed alien in a land whose language he did not speak. But he had not just survived, but carved out a decent career as an art teacher. Married with children, he was outwardly content. If he had coasted through the rest of his years on psychological auto-pilot, his life would still have been deemed a triumph against the odds.

Yet in his mid-forties, Blik did something that should give hope to anyone drifting towards obscure middle age. Prompted by two twists of fate – one a chance encounter; the other a revelation by his dying mother – he ignited that spark within himself. And what a blaze he started. Today, Blik – concentration camp survivor and refugee – is one of Britain’s most successful sculptors. His bronzes adorn museums, banks and hospitals. He is a past president of the Royal British Society of Sculptors. And this week it was confirmed that he will create a large sculpture for the multi-billion redevelopment of King’s Cross. His story obviously has heroic aspects that none of us could emulate. But at another level, that of a middle-aged man who decided to make the most of his latent talent, his example should inspire anyone who has ever started a sentence with those defeatist words: “I could have been … if only”.

Blik was born in Amsterdam in 1939. The worst possible time and place to be a Jewish baby. One of his earliest memories is of his mother sewing the yellow star on his clothes. “Why do we wear that?” the three-year-old asked. “Because we are special people,” she replied. The Bliks heard the ominous bang on the door in 1943, when Maurice was four. Like Anne Frank’s family, discovered a few streets away, they were sent first to the Westerbork concentration camp. From there Maurice’s father was deported to Auschwitz. They never saw him again. Maurice himself contracted a mastoid infection and might have died but for primitive surgery by an inmate. “He carved away a chunk of my skull as best he could, and saved by life,” Blik says.

Then, in late 1943, with his sister, mother and grandmother, he was sent to Belsen. “My mother was pregnant,” Maurice recalls. “The child, a girl, was born in Belsen – and she died there.” Belsen was not, officially, a “death camp”. But with food growing scarcer and sanitary conditions increasingly dreadful, death was ever present. “As a four-year old I thought that what happened in Belsen was what life was all about,” Blik says. “I wasn’t aware that it was horrific to have to drag dead people out of their bunks.” So little food was available that people eked out a crust over several days, sleeping with it under their heads. “Of course, when they died the first person to find them could take the bread,” Blik recalls. “I became very good at telling when people were dying. We had to survive.”

Belsen was liberated in April 1945. But by then the Bliks had been moved. “I think the Germans wanted to clear up the evidence,” Blik says. “So two trains left Belsen packed with prisoners. We were on one.” They were locked in for two weeks, people dying all the time, until this nightmare journey ended near Leipzig. “I looked out of the window and saw Russian Cossacks galloping on horseback towards us. That was it. Our liberation.”

Curiously, Blik’s flat is strewn with sculpted horses’ heads. He has always enjoyed making them, without wondering why at least until he started working on a project with a film-maker. “One day she unearthed some footage of Cossack troops on horseback,” he says. “she said to me: ‘Look, they are just like the horses’ heads you are always making’.”Blik’s mother had relatives in England, so she and her children were sent there to make a new start. “I didn’t know a word of English except the address of an aunt in Cheltenham. The aunt, though, was horrified by us, mainly because when she put food on the table my sister and I would just pounce on it. We hadn’t picked up many social graces in Belsen.” The six-year-old Maurice not only had the bloated stomach of the malnutritioned, but impaired hearing, the result of the, primitive operation in the camp. That needed more surgery. School was not only incomprehensible but unpleasant. “I remember being in the playground on my first day with a circle of kids round me, jeering and laughing. Not nice.”

But a boy who had survived Belsen could survive some commonplace school bullylng. Within three years Blik was so proficient in his new language that he sailed through ll-plus and into a grammar school. There he did well. It seemed that he was going to fulfil the dream he had held since having thatlife -saving operation in Westerbork – that he would himself become a doctor and save other lives.

It was not to be. At 16 it dawned on Blik that he would never be able to deal with the ill or dying. “It was odd. As a five year-old I had pulled dozens of dead bodies out of bunks. Ten years later, I couldn’t face dealing with death.”

Instead he turned to art. He went to Homsey College of Art, taught in Essex schools, then came back to Hornsey as a tutor. And that’s where he would be to this day, had fate not intervened once more in his extraordinary life. Blik had married a potter. “I had done a bit of sculpture early on, but when I met her I gave her my studio,” he recalls. “Essentially, I lived art vicariously through her. For whatever reason, I stopped creating my own work.”

Until, that is, one of his wife’s buyers called to discuss the commission of a ceramic horse’s head. Who knows what button in Blik’s subconsciousness was pressed by that choice of subject. “I experienced a rush of blood,” he recalls. “I got some clay, made half a dozen horses’ heads, brought them to the man and said: ‘This will give you some ideas.’ He said: ‘Where did they come from?’ I replied: ‘I just made them. And he said: ‘Well, why don’t you make the head.’ It was a watershed. I hadn’t done any sculpture for 15 years. Unfortunately, my wife was sitting there, going: ‘Er, I’m the artist’.”Awkward moment? “Extremely,” Blik replies. “It was the beginning of the end of our marriage.” But it was also the start of

the life of Maurice Blik, sculptor.

There was one other curious rite-of-passage for Blik to go through before his creative gifts were liberated. “A little while before my mother died in 1986,” he recalls, “she said to me: ‘I don’t know if we did the right thing in making you right-handed.’ I said: ‘What are you talking about?’ She said: Left handed people were thought to have something wrong with them. So when we saw you using your left hand, we forced you to write righthanded.’ I had gone through my life doing everything right-handed, feeling awkward, and not knowing why.”

Most people, discovering this in their forties, would have shrugged and said “can’t be helped now”. Not Blik. “I stopped using my right hand. I spent two days just copying out things with my left hand. It felt physically odd, of course. Yet the minute I started it seemed as if my brain had connected with my hand for the first time. Ideas flowed. It drove colleagues mad, because it was months before my writing was legible. But I felt as though filters had been removed from my brain.”

Blik’s creativity since the mid-1980s has been both prodigious and profoundly moving. His huge bronze figures typically emerge from black metallic masses like butterflies from cocoons, and stretch upwards, their fingers often just touching some mysterious shining object above them. You don’t have to be an art critic to grasp the metaphor. This might be the artist emerging from his dark past. Or perhaps it’s the

indomitable human spirit, rising from apparent devastation to reach for the beauty that will not be crushed.

Only in one terrifying work does Blik lift the lid on the waking nightmare of Belsen. In 1999 he created a bronze of a ferocious hound: a grotesque black beast, fully 8ft long. It’s no surprise to learn that this

ghastly apparition had been dredged straight from his childhood memories, like a kraken summoned from the abyss. “One day a camp guard came into the hut with her enormous guard-dog,” Blik says. “I was sitting on the

floor, and she started to torment me by eating this juicy apple. I knew what would happen if I reacted. So I sat there motionless. Then she put the core on the floor, set the dog to guard it, and wandered off. The dog would have ripped me to pieces if I had tried to take it. When she came back she laughed and began to grind the apple into the floor with her boot. Well, a few years ago when I had a West End

show, it occurred to me that I needed to create this dog.” To have experienced such sadism at five, and yet be capable of creating sculptures that convey a huge optimism about mankind – this suggests that Blik has a remarkable capacity for detecting glimmers oflight in a dark world. “Oh, I’ve always had an optimistic view of the world,” he says. “The Holocaust was a terrible event. But the people who came out of it have often gone on to achieve phenomenal things. That’s what I want to show.”

Karl Popper

Popper text

Expertise: a meta-frame

Expertise itself is seldom defined, making it difficult to know what to make of those who at best ignore and at worst ridicule experts opinions or advice. If it is discussed it assumes that expertise improves step-by-step with little more than disciplined and repeated practice. This is summed by the injunction that “Practice makes perfect”. Practice doesn’t necessarily make perfect; it makes permanent. Moreover, closer examination of the way expertise is actually acquired reveals that it occurs unpredictably across many dimensions simultaneously and in a non-linear manner. In summary expertise is the culmination of breadth and depth of experience. The difference between how novices and experts operate can be tabled as follows:

| NOVICES (outsider – exoteric view) | EXPERTS (insider – esoteric view) | |

|---|---|---|

| Problems | work backwards from known solutions, which they try to remember | work forwards with the unknown, re-formulating problems |

| Holistic Perspective | think dichotomously in terms of basic facts and their direct application | operate metaphorically: as reflecting, theorising and modelling practitioners |

| Errors | believe they have to copy others and in an error-free manner | edit their performance,through trial and review |

| Authority | rely on confusion to authorize their ignorance | rely on the authority of ignorance to validate and voice their confusion |

| Thinking | report that they have to think (with their brain) in their head | think with pencil in the hand on paper |

| Graphicacy | use paper to record the results of thinking | use paper to clarify thinking |

| Criticism | tend to avoid because it’s seen as an attack on their personal integrity | accept as a pre-condition,for the growth of knowledge |

| Task Focus / Structure | single, linear and seemingly simple: difficulty in flipping from fact to fact and between fact and fiction |

multiple, schematic and seemingly complex: can and do flip between facts and fictions using imagination |

| Pedagogic Model | authoritarian – hierarchical | authoritative – collegial |

If the only tool you have is a hammer!

The ‘argument’ is simple: if the tools that are currently being used to handle a problem are not resolving it, then the tools need to be changed. Here three gategories of tools are involved: person-driven, object-driven and root metaphor-driven.

Person-driven

The poet John Donne proclaimed long ago “… no man is an island”. In keeping with this sentiment the ‘unit of discourse’ on this web-site is not the de-contextualised individual but individuals acting in social contexts. It follows that there is a need to agree on working definitions of three key ‘ordinary language’ terms, communication, common-sense and interaction.

• Communication: the shared interpretation of action

• Common-sense: when what we see agrees with what we hear such that we feel comfortable with the common message from the different senses.

• Interaction: exists, primarily in two forms weak or strong.

• weak interaction – where neither party to the action changes in any respect as a result of the action.

• strong interaction – where both parties to the action change in some respect.

• [it is recognised that a mixed form exists – where one party changes but the other doesn’t.]

The major difficulty in appealing to common-sense to settle matters under dispute is that common-sense is itself seldom defined. Both the Ancient Greeks and Rene Descartes defined common-sense (operationally) as when the messages from an individual’s different sense are in harmony.

The normative definition of common sense as when everyone agrees fails to overcome the objection that one person’s common-sense is often another’s nonsense, which is why sometimes there are hung juries. It is reported that Bertrand Russell, quoted by Lawrence Peter, well made this case when he said that ‘even 50 million people can be wrong’.

It is generally assumed that when two speakers use the same words, the words hold the same meaning for each. If, however, this were to be the case then it would seldom take long for novices to become experts and experts themselves using the same vocabulary would seldom disagree amongst each other.

Defining communication as the shared interpretation of action can be represented graphically as the intersection of two overlapping personal action circles. This is not the conventional definition: the transmission of a message from a transmitter to a receiver. This mechanistic model offers three explanations for poor communication; interference between transmitter and receiver, fault with the transmitter or fault with the receiver, or various combinations amongst all three. This normative definition promotes many opportunities for much fruitless ‘research’ for and endless debates over the causes of lack of personal progress. It is a totally inappropriate model in the world of pedagogy.

Object-driven

Four objects are used both literally and metaphorically :

• The jigsaw puzzle: embodies the fact that the different parties to the interaction each have some pieces of the overall picture, that we need to make sure the pieces are face up and then placed together to see what overall sense can be made of the seemingly nonsensical pieces the world throws at us to create intractable problems

• The ice-berg: captures the fact that beneath the visible, audible and tangible surface problems there are invariably deeper / hidden problems.

• The tetrahedral or four-faceted pyramid; embodies the view that human beings are not the sum of separate physical, intellectual, emotional and social parts, but that these are facets of a single integral whole. One implication of this image is that if one facet is found to be out of kilter, other facets will, on closer probing, be found to be out of kilter too.

• The computer: captures two notions.

• the brain is hard-wired, but unlike the computer it is hard-wired to be more adept with one or other hand.

• just as the computer uses software to run tasks, the human brain is programmed -amongst Anglo-Saxon speakers- by the language of human rights. This image hints at the nature of the mental gymnastics natural left-handers have to perform living in a right (handed) world.

Pepper’s root-metaphor world-view

As long ago as 1942 Stephen Pepper published a book entitled World Hypotheses: A Study in Evidence, in which he made four claims:

• nobody can be convinced against their own (better) judgment,

• radical destruction is more difficult than construction: that is, it’s not so easy to get to rock solid foundations. Yet unless we do we’re building on shifting sands!

• that amongst all the objects in the world there are the hypotheses that we hold about how the world itself ‘works’,

• there are three cognitive attitudes: dogmatism, utter scepticism and reasonable scepticism.

There are several set of implications, (in agreement with Karl Popper). The first set:

• there is no single totally objectively neutral view of the world,

• all observations are biased (that is, inevitably theory laden, no matter how implicitly held or how inarticulately expressed)

• the very facts we choose to accept as evidence vis à vis some contentious issue are impelled by our world views. This explains, in a nutshell, why experts working in the same field so often disagree amongst themselves – it’s not so much that the vocabulary is different but the images and actions which lie behind the vocabulary which are.

The second set:

• changing the position of dogmatists entails challenging, but indirectly, their reliance on self-evident principles, immutable truths and infallible authority.

• utter sceptics, in so far as they claim not to believe in anything, are dogmatists by another label.

• reasonable scepticism is the hallmark of doubters waiting to be convinced by the quality of their self-validated evidence.

Pepper’s major contribution, was, however, to note that the potentially infinite number of hypotheses collapse, under close scrutiny to just six, which he named Animism, Mysticism,

Pepper’s framework explains why one expert’s facts are another’s highly interpreted evidence.

An alternative depiction is a 3-dimensional space in which (a) the ‘con’ is deleted from Contextualism to give Textualism (b) at the centre of the three other overlapping relatively adequate world views – in the horizontal plane and (b) placing the other two relatively inadequate overlapping world views in the vertical plane. This acknowledges the fact that ‘cognitions’ don’t exist independently of ‘emotions’.

Pepper’s work, in many respects, pre-dates both Mary Douglas’s (1987) How Institutions Think: Routledge, Kegan & Paul and George Kelly’s Personal Construct Theory (1955) London; New York: Routledge. In Kelly’s, Pepper has categorised personal constructs into six root world-views.

Peppering the problem: Stephen Pepper

- there are three cognitive attitudes: dogmatism, utter scepticism and reasonable scepticism

- we can’t convince people against their own better judgment

- radical destruction is more difficult than construction: that is, it’s not so easy to get to rock solid foundations. Yet unless we do we’re merely building on shifting sands!

- that amongst all the objects in the world there are the hypotheses that we hold about how the world itself works.

Pepper’s insight, was, however, to note that the potentially infinite number of hypotheses collapse, under close scrutiny to just six, which he called Animism, Mysticism, Formism, Mechanism, Contextualism and Organicism. The critical features of each, according to Pepper, can be tabulated as follows:

| World-view | Descriptive Root Metaphor | Explanatory Value | Tools | Questions | Leads to |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animism | common-sense man | grossly inadequate | emotions | What is the spirit of X? | infallible authority |

| Mysticism | the common emotion of love | How can we appease the gods? | indubitability | ||

| Formism | shoe last – template acorn-oak – essence | adequate | nouns | What is truth..the essence of X, of Y or of Z? | mechanism |

| Mechanism | machine: lever-fulcrum | How does X affect Y? | contextualism | ||

| Organicism | plant / animal | What are the links amongst A, B & C? | creative imagination | ||

| Contextualism | doing, enduring, enjoying | verbs | Plus ça change, plus la même chose? | operationalism |

Pepper’s root metaphor framework allows us to see why one expert’s facts can be regarded another’s highly dubious and / or irrelevant opinion.

Glossary

| A | E | I | O | U |

| B | F | J | P | V |

| C | G | K | Q | W |

| D | H | L | R | X |

| M | S | Y | ||

| N | T | Z |

Child Helping Agencies

As long ago as 1971 Lourie & Lourie summarised child-help [… ] as being a confused set of fragmented services. They stated that we parcel children out to institutions on the basis of social, legal, and sometimes diagnostic labels that neither describe the child nor offer a prescriptive base for treatment. They said most observers agree on the following:

- Service delivery arrangements are geared more to professional and field needs than to children’s,

- We deal with crises more than prevention,

- We reach only a fraction of the need population,

- We know that childhood difficulties begin in infancy, yet our child programs concentrate on events beginning after this critical period,

- Our programs do not follow research findings: we concentrate on those likely to be cured rather than on tough cases.

(American Journal of Orthopsychiatry vol. 40, No. 4 July, 1970 pp 684-693)

Although they were talking about the scene in America many years ago, much the same could still be said about provision in the UK and of today.

Cognitive processes: memory, perception, learning (concepts), and problem solving and understanding.

Standard textbooks on psychology have separate chapter headings for topics such as memory, perception, learning, problem solving and understanding.. Each chapter will then be further subdivided into topics and each topic into sub-topics. The major misconception is to assume that just because humans can be described this way in textbooks that this is the way the world really is, as the following brief quotations make plain.

Concepts: Bolton, from The Psychology of Thinking, “A person does not form a concept then apply it; he forms it through application.” p.150

Memory, Perception and Learning: Herriot, from The Attributes of Memory., in the context of experimental psychology states: “ ….It will become evident that memory processes, cognitive processes and linguistic processes can only be distinguished on the basis of the experimental task, not on the basis of their intrinsic differences” (p179).

Common-Sense

There is a major difficulty in appealing to common-sense to settle matters under dispute: common-sense is itself seldom defined. It might be argued that in the criminal justice system it is indeed defined operationally in terms of the procedure which allows a verdict to be reached by a jury of 12 randomly selected ‘ordinary’ citizens. This normative definition however, fails to overcome the objection that one person’s common-sense is often another’s nonsense, which is why sometimes there are hung juries. Bertrand Russell, quoted by Lawrence Peter, well made this case when he said that ‘even 50 million people can be wrong’.

Both the Ancient Greeks and Rene Descartes had defined common-sense (operationally) as when the messages from an individual’s different sensory systems, principally sight and sound, transmit the same, that is, common, message to the brain. It follows that non-sense exists when what is seen disagrees with what is heard.

Communication

It is generally assumed that when two speakers use the same words, the words hold the same meaning for each. If, however, this were to be the case then it would seldom take long for novices to become experts and experts themselves using the same vocabulary would seldom disagree amongst each other.

Communication is defined here as the shared interpretation of action. It can be represented as the intersection of two overlapping personal action circles. This is not the conventional definition which emphasizes the transmission of a message from a transmitter to a receiver. This mechanistic model offers three explanations for poor communication; interference between transmitter and receiver, fault with the transmitter or fault with the receiver, or various combinations amongst all three. As such the model allows many opportunities for fruitless ‘research’ for and endless debate over the causes of lack of personal progress. It is a totally inappropriate model in the world of pedagogy.

Complexity Theory

In essence complexity theory treats entities as though they are a system then explores how as systems they acquire the ability to bring order and chaos into a special kind of balance. This balance point, is often called the edge of chaos. Some of the key features of complexity theory are:

- there is no single cause for any given phenomenon,

- that small differences in initial beginnings give rise to large later effects,

- a large number of independent ‘agents’ interact in a great number of different ways,

- the richness of the interactions induces the system as a whole to undergo a spontaneous self-organization,

- these self-organizing systems are adaptive, turning whatever happens to their advantage.

Counselling-Through-The-Curriculum

Given, as some argue, the need for pupils to be counselled, as well as taught, atomists construe the task as one of time management; when to bolt it onto or squeeze it into pre-existing curriculum activities. Holists on the other hand are able to treat all activities as being potentially ‘therapeutic’. An exemplary account of such an approach in the Primary School context is to be found in a paper by Wooster & Carson (1979), Self Concept and Reading Skill. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling. This later approach can be labelled counselling-through-the-curriculum. In essence it involves the public processing of private predicaments.

Education

There is no universally agreed definition of what education is. But that is not the overarching problem. The overarching problem is the framing one: what counts as a useful definition of anything, for as Karl Popper suggested there are three types of definition:

“What is …?” essence questions. These, he suggested, are ultimately resolved by reference to an authority, regarded as infallible, who pronounces one way or another.

“What are the links amongst x, y, and z? Relational questions, although, one step better than essence questions, by themselves they still don’t allow us to distinguish between correlation and cause and effect on hand result of an underlying common-core on the other.

“What happens if I do X rather than Y? operational questions” These questions offer more, since they invite action, not endless sterile debate.

For pedagogues there is no problem of defining education: they (often implicitly) make use of a distinction between the Form of an activity and its Content. For example, for them it is not what is studied that makes an enterprise scientific but how it is studied. Thus using the ‘technology of the grid’ we can define education in essence, relational and operational terms as follows:

| The politics of techno-linguistic framing | Form | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed | Varied | ||

| Content | Fixed | conditioning | propaganda |

| Varied | disciplines | education | |

This qualitative definition distances itself from the notion that education is an entity to be delivered through the implementation of national curriculum documentation.

Evaluation

Assessment Models

It is relatively easy to devise ‘a test’ to demonstrate differences amongst individuals and their abilities. Indeed there is a multimillion pound business devoted to differentiating amongst individuals. What is less well known is that there are four assessment models: their validity as evaluation tools is, however, dictated by context.

- Assessing by testing (using psychometric norm-referenced tests),

- Teaching then assessing-by-testing (using traditional teaching criterion referenced tasks),

- Testing, teaching then assessing-by-testing (using the zone of proximal development model),

- Testing, teaching then assessing-through-teaching (using the role reversal criterion)

The first three models are fairly self-explanatory. They represent, respectively, occupational performance tests, traditional teaching practices, and programmed instruction.

The ‘Testing, teaching then assessing-through-teaching’ model may need further explanation. In this model, only when those who are being assessed can teach others what they have just learned, whether peers, sometimes parents or occasionally ‘teachers’, can they be deemed to have mastered the material. This model is concerned not simply with seeing how well individuals perform on any given test or series of tests but with seeing how much more they can do with assistance (ie instruction or teaching), and then seeing how well they perform when asked to induct others into their newly acquired knowledge.

The pedagogical question is, ‘which individuals continue to improve and assume the role of the teacher, which stay at that new level, and which fall back to the initial base-line. This ‘model’ of evaluation answers the pedagogical question, “How should we work playfully with learners to promote their education?”. The question ‘What should we teach them?’ is inextricably tied up with this question. Few if any psychological, and virtually no education, assessments are conducted within this framework.

Pedagogical evaluations for education, medico-legal or legal purposes

“What is a pedagogical evaluation for whatever purpose?”. Simply stated it is an investigation which aims to identify the obstacles both in the individual and in the system which prevent learners, clients or offenders acquiring the ability to become self-sufficient, mutually interdependent and respectful, responsible citizens.

The tools for conducting such evaluations are not the norm-referenced ability oriented psychometric tools of psychologists. They are the criterion-referenced functional metaphorical tools of the jig-saw puzzle, the ice-berg, the tetrahedral pyramid and the computer. In essence pedagogues view teaching and testing as the two sides of the same page.

Expertise: A Meta-Frame

Models of expertise are linear and assume performance improves step-by-step with little more than disciplined and repeated practice. This is summed by the injunction that practice makes perfect. However, closer examination of the way expertise is actually acquired reveals that it occurs unpredictably across many dimensions simultaneously and in a non-linear manner. The difference between how novices and experts operate can be tabulated as follows:

| NOVICES (outsider – exoteric view) | EXPERTS (insider – esoteric view) | |

|---|---|---|

| Problems | work backwards from known solutions, which they try to remember | work forwards with the unknown, re-formulating problems |

| Holistic Perspective | think dichotomously in terms of basic facts and their direct application | operate metaphorically: as reflecting, theorising and modelling practitioners |

| Errors | believe they have to copy others and in an error-free manner | edit their performance,through trial and review |

| Authority | rely on confusion to authorize their ignorance | rely on the authority of ignorance to validate and voice their confusion |

| Thinking | report that they have to think (with their brain) in their head | think with pencil in the hand on paper |

| Graphicacy | use paper to record the results of thinking | use paper to clarify thinking |

| Criticism | tend to avoid because it’s seen as an attack on their personal integrity | accept as a pre-condition,for the growth of knowledge |

| Task Focus / Structure | single, linear and seemingly simple:difficulty in flipping from fact to fact and between fact and fiction | multiple, schematic and seemingly complex:can and do flip between facts and fictions using imagination |

| Teaching- Learning Relationships | authoritarian – hierarchical | authoritative – collegial |

Facts vs Evidence

If facts really did speak for themselves there would seldom be any disagreement amongst any of us over anything, and especially amongst experts operating in the same field. That disagreement does exist even amongst experts themselves testifies to the fact that despite their expertise each dissenting party operates with implicitly different reference frames. This is why for some the words dyslexia, dysgraphia, ADHD, depression, or criminality refer to factual entities whilst for others they are merely short hand labels for sets of attributes reflecting the labeller’s world-view.

The over-arching frame work has long been provided by Karl Popper, who has explained why there are no such things as theory-free observational facts and by Stephen Pepper who has ‘explained’ why what are regarded as theory-free facts by one person are regarded as highly interpreted evidence by another.

Graphicacy

The generic label for putting pen to paper, ‘graphicacy’, includes the areas traditionally called literacy and numeracy and drawing. Thus, dysgraphia is a useful short-hand descriptive label for those putting their thoughts on paper with seemingly effortless ease. A seminal account of how to establish functional literacy is to be found in Kohl’s, Reading: How to; Penguin. The key, he argues, is to identify how children approach the task of reading children: do they try to avoid the task, are they reluctant, do they hesitate, or are they O.K., keen, or enthusiastically immersed?

Pedagogy privileges graphicacy over talking and listening, if for no other reason than, were we to restrict communication to the latter we will be denied the opportunity to picture what we see. The same qualitative categories identified by Kohl with respect to reading apply with equal force to graphicacy.

Handedness

Laterality

Handedness has generally been studied quantitatively in terms of degrees of laterality. These studies have been confounded by questions about crossed laterality, that is, eye-hand-foot dominance.

Writing and adept hand

Here handedness is studied qualitatively in terms of hand functionality. Two forms of handedness exist: a writing hand and an adept hand.

The writing hand is simply observed by noting which hand the pen is held in. The adept hand is noted by observing which hand handles unfamiliar complex manipuilo-spatial tasks with seemingly effortless ease.

If common-sense were to prevail, everyone would write with the adept hand. For a variety of complex reasons this is not always the case. Since it is writing that defines humans as being uniquely different from every other animal, and it provides the measure of academic ability and school effectiveness, the consequences of writing with the non-adept hand are far-reaching; both for the individual and society at large.

Converted / latent handedness

Converted handedness has been defined by Barbara Sattler as when individuals, for whatever reason, have ‘learnt’ to use their right hand as their dominant hand when their left hand is their natural dominant hand. Latent handedness is when the adoption of the right hand (generally) as the dominant hand has taken place unbeknownst to the individuals or individual’s family.

Humour And Humiliation

Pedagogy is a serious business. We do, however, confuse seriousness with solemnity to the detrimental well-being of learners. Indeed, so confused are we about ‘controlling’ learners that, in true Victorian fashion, we still wish, in the case of children, for them to be seen and not heard and resort to punishment or the threat of it when they don’t conform. One of the more insidious forms of punishment, whether intended or not, is perceived humiliation. It’s worth quoting two views on humiliation:

First: “Human beings, however they have been socialized, do share a susceptibility other animals lack: to a particular sort of pain. They can be humiliated by the violent disruption of their patterns of belief and cherished values.

…We have ‘a common susceptibility to humiliation’. We are vulnerable to it by virtue of the beliefs and attachments that can be belittled and exposed to ridicule; and because a person can be coerced into doing and saying and sometimes even thinking things ‘which later she will be unable to cope with having done or thought.’ As Rorty also says, ‘… the best way to cause people long lasting-pain is to humiliate them by making the things that seemed important to them look futile, obsolete and powerless.”

Norman Geras (1995) Solidarity in the Conversation of Humankind: The Ungroundable Liberalism of Richard Rorty: Verso; London, New York (p. 52)

Second: “If a child in our own society does not laugh, it is a matter of some concern. Laughter frequently accompanies enjoyment, indeed it is an expression of enjoyment. Children will laugh in a game without anything in particular striking them as funny. They will laugh at a clown, at a man with a funny hat, or at a funny sounding word. Children cope with their problems by laughter, transforming the painful into the enjoyable, poking fun at authoritarian adults. It is only rarely that misfortune permanently dampens their spirit.”

Lloyd , D..I., (1985) What’s in a Laugh? Humour and its educational significance. Journal of Philosophy of Education vol.19 no.1 pp 73-80

Marc Gold’s competence-deviance hypothesis offers one positive way of capitalizing on those attributes which serve to identify us as being different and therefore potential victims of humiliation and as objects of others’ derisive humour. Searching for and then acknowledging an individual’s competence allows us to tolerate their deviancies with greater equanimity.

Interaction

Strong vs weak

Interaction is when two or more individuals affect each other’s actions. Bijou distinguished between two types, strong and weak (or dynamic or static). Strong interaction, occurs where all parties to the action change in some fundamental respect through the action. Weak interaction occurs where none of the parties to the action change in any fundamental respect through the action. Mixed interaction occurs when some parties to the action change but other parties do not.

Exploratory vs exhortatory

Synthesizing the archetypal roles of parent, child and adult with Descartes’ definition of common-sense we can chart two proto-typical modes of interacting; exhortatory vs exploratory – whether the inter-actors be parent-child, teacher-pupil or novice-expert.

| Facets | Senses | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Status | Visible | Audible | Tangible |

| Parent | No! You’ve not seen it right.Look at this, closely | No! You’ve not heard it rightListen to me, carefully | No! You’ve not got it right.Take this, it’s good for you. |

| Adult | Let’s see | Let’s say | Let’s make… |

| Child | Please. Show me, again | Please. Tell me, again | Give me; I want it now |

Learned Helplessness:

Learned helpless is a term coined by Seligman in the 1960’s. It refers to the case wherein individuals are repeatedly exposed to situations beyond their control. It is ‘measured’ in terms of:

- passivity

- decreased interest

- reduction in taking the initiative.

Learned helplessness can be changed by:

- engaging the ‘helpless’ in setting realistic and attainable goals,

- providing sufferers with the evidence to allow them to recognize the control they do have,

- helping them develop realistic understandings of the causes for their actual successes and failures,

- focus on observable improvements.

A critical feature of learned helplessness is that events are seen as being independent of action and therefore beyond self control. Contrary to common practice, a sense of acquired control is not achieved simply by being told to have greater confidence or to assert self-control.

Learning To Learn

Harlow, working in the 1940’s and 50’s coined the term ‘Learning-to-Learn’. He demonstrated that even non-verbal (non-human) animals as well as verbal and non-verbal children could learn to master a conceptual oddity task. The learners were presented with sets of objects which allowed them, without knowing why or how, to learn how to learn. One critical feature of learning-to-learn is that it’s success depends not on the ability of the learner to articulate either the purpose of what they’re about to do nor how they’re doing it but simply by acting with the prescribed learning-sets material.

Lunzer (1971) took this one step further by asking children to explain their actions and to turn the tables by testing the instructor. Unsurprisingly although children aged 3 to 4 could learn to select the odd object from a set of three, it wasn’t till they were 7 or 8 that they were able to ‘test the teacher’.

Levy, working in the late 60’s early 70’s with undergraduate psychology students, engineered a similar phenomenon by demonstrating that such students could learn (to learn) how to write commendable essays. In the shift from novice to expert status the students experienced four phases:

- Blissful ignorance: where although they thought they knew the answers they didn’t even know the important questions.

- Utter confusion: caused by the mis-match between their earlier view and their recently acquired one and by the mis-matches amongst the experts themselves, which they were expected to resolve.

- Clarification of issues: when they were able to, at least, speculate on what the critical issues might be, even though they could not, initially, resolve them.

- Resolution of issues: brought about by further conjecture, higher-order synthesis or re-framing.

The two pedagogic lessons are, first that we are all quite properly confused when trying to grasp something we initially can’t grasp; and second that those with no confidence in their ability to formulate the nature of their confusions are unlikely to persevere long enough to be able to work through their difficulties. The counter-intuitive message is that confusion is not an obstacle to comprehension, not something to be avoided: on the contrary it is a step towards clarification of conceptual issues. In short it is not evidence of stupidity but of engagement with conceptual difficulties.

Two types of paradox are of concern to this site; policy and instructional. Policy paradoxes exist wherever policy implementation exacerbates the very problem the policy was intended to solve. Instructional paradoxes exist every time the implementation of clearly defined instructional goals goes awry. These paradoxes extend all the way from attempts to raise educational standards, reduce addictive (drug) behaviour to reduction of knife crime and recidivism rates. If individuals were to conduct themselves because of the clarity of others’ clearly stated and carefully documented targets then all individuals should be capable of conforming to those targets. Yet they don’t!

Each paradox can be relatively simply resolved. Policy paradoxes are resolved by regarding ‘policy’ as little more than ‘theory’ under another name. Instructional paradoxes are resolved by regarding any set of tasks as multi-faceted and multi-purposed and re-framing the problem.

Pedagogy

Why adopt pedagogy and not psychology as the appropriate ‘discipline for solving intractable personal problems? An etymological answer comes from looking at the first acknowledged uses of both words. The on- line source http://www.etymonline.com offers the following:

Pedagogy: 1387, “schoolmaster, teacher,” from O.Fr. pedagogue “teacher of children,” from L. paedagogus “slave who escorted children to school and generally supervised them,” later “a teacher,” from Gk. paidagogos, from pais (gen. paidos) “child” (see pedo-) + agogos “leader,” from agein “to lead” (see act). Hostile implications in the word are at least from the time of Pepys. Pedagogy is 1583 from M.Fr. pédagogie, from Gk. paidagogia “education, attendance on children,” from paidagogos “teacher.”

Psychology: 1653, “study of the soul,” probably coined mid-16c. in Germany by Melanchthon as Mod.L. psychologia, from Gk. psykhe- “breath, spirit, soul” (see psyche) + logia “study of.” Meaning “study of the mind” first recorded 1748, from G. Wolff’s Psychologia empirica (1732); main modern behavioral sense is from 1895.

On these grounds alone one obvious difference between the two is that the emphasis in psychology is on the individual whereas in pedagogy the emphasis is on the interaction between amongst individuals, one of whom can be called novice and the other expert.

A more empirical answer is that just because something works in the psychological laboratory does not mean that it will work in the hurly-burly of the classroom. Pedagogy is a discipline in its own terms and not founded in or dependent on the disciplines of psychology, sociology, philosophy or history. It can be operationally defined as when novice and expert each interact in a reflecting, theorising and modelling manner.

Problems

Framing

Framing a dilemma, decision, doubt or difficulty in terms of a ‘problem’ is an admission that no solution currently exists for the problem holder. This does not necessarily mean that a solution has not been found by another, but unknown, problem holder. Thus when someone says, there is no solution to their problem, what they almost certainly mean is that it is they personally don’t yet have a solution, not that no solution exists.

What is formulated as a problem and how it is formulated depends on the status of the formulator as novice or expert. For, whereas novices tend to tackle a problem as though it were the whole of the problem experts place a problem in a wider context. Placing problems in wider contexts is called ‘framing’ the problem. Indeed it is the way problems are framed which defines individuals as novices or experts.

Problem Formats

Krutetskii made a key contribution (in the field of Mathematics Education) to the problem solving literature by distinguishing amongst three problem formats:

- Problem buried in information : information was presented with no formally identified problem or explicitly stated question,

- Explicit problem buried in extra information: the question or problem was explicitly stated but presented with additional information,

- Explicit problem but presented with missing information: problems were explicitly stated, but presented with not enough information to solve the problem.

On the basis of these three types of problem he was able to demonstrate the key role of ‘mental structure’ in identifying able, capable and incapable children and in how memory works in a constructive rather than photographic manner.

Perspectives

Holistic vs atomistic

Psychology is notorious for emphasizing the differences amongst individuals then fragmenting individuals themselves into different components – physical, intellectual, emotional and social – and treating them as capable of being separately manipulated. As a profession psychology then uses these different components to justify separate institutional resources and structures.

A holistic perspective emphasizes the similarities amongst individuals then regards individuals as being integral wholes, with the physical, intellectual, emotional and social merely as facets reflecting observers’ interests. The tetrahedral or four-faceted pyramid best represents this perspective. One clear implication follows: if one facet is found to be out-of-kilter the other facets, on deeper probing will probably be found to be out of kilter too.

World-view perspectives

As long ago as 1942 Stephen Pepper published a book entitled World Hypotheses: A Study in Evidence, in which he claimed:

- there are three cognitive attitudes: dogmatism, utter scepticism and reasonable scepticism

- we can’t convince people against their own better judgment

- radical destruction is more difficult than construction: that is, it’s not so easy to get to rock solid foundations. Yet unless we do we’re merely building on shifting sands!

- that amongst all the objects in the world there are the hypotheses that we hold about how the world itself ‘works’.

Pepper’s insight, was, however, to note that the potentially infinite number of hypotheses collapse, under close scrutiny to just six, which he called Animism, Mysticism, Formism, Mechanism, Contextualism and Organicism. The critical features of each, according to Pepper, can be tabulated as follows:

| World-view | Descriptive Root Metaphor | Explanatory Value | Tools | Questions | Leads to |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animism | common-sense man | grossly inadequate | emotions | What is the spirit of X? | infallible authority |

| Mysticism | the common emotion of love | How can we appease the gods? | indubitability | ||

| Formism | shoe last – template acorn-oak – essence | adequate | nouns | What is truth..the essence of X, of Y or of Z? | mechanism |

| Mechanism | machine: lever-fulcrum | How does X affect Y? | contextualism | ||

| Organicism | plant / animal | What are the links amongst A, B & C? | creative imagination | ||

| Contextualism | doing, enduring, enjoying | verbs | Plus ça change, plus la même chose? | operationalism |

Pepper’s framework allows us to see why one expert’s facts are another’s highly interpreted evidence.

Personal Predicaments And Their Problematic Solutions

There are broadly speaking two views of what life is: problem-laden and error-free. The first acknowledges that living entails being confronted with a never ending series of puzzles, problems, predicaments and paradoxes or doubts, difficulties, dilemmas and decision. Such individuals generally accept the problematic nature of conjectured solutions.

The error-free view anticipates a difficulty-free existence provided one adheres to rule-driven certainties. Acting in an error-free manner entails making risk-free decisions. Since life is seldom like this such individuals interpret their resulting experience as evidence of either their or others’ stupidity or lack of clarity.

It is not surprising that communication fails when error-free believers interact with problem-laden practitioners.

Questions

The type of questions asked serves to measure intellectual curiosity. Indeed questions provide a better measure of intellectual ability than answers offered. It follows that when evaluating intellectual ability it is better to place individuals in situations which provides material inducing them to ask their own questions.

If, however, we’re wedded to the idea that others should learn to answer our questions and we continue to question others too quickly, even before they have had time to formulate their own questions and then, only when their answers are wrong and never when they are correct, others will soon catch on that they are regarded as stupid!

If we, however, accept the legitimacy of questioning others we should question others even when they offer apparently correct answers! For others should be able to resist our counter-suggestions if they really know what they’re talking about. This alternative view of questionning upsets the implicit ‘knowledge is power’ relationship inherent within the existing novice-expert teaching-learning model.

Reward-Punishment System

Every institution or organisation, whether school or family, has its own reward-punishment system no matter how implicitly held or explicitly formalised. If questioned each institution would propose its own (theoretical) justification for its own practice.

However, the very notion of ‘rewards and punishments’ is fraught with major practical and conceptual difficulties. The major conceptual difficulty is that technically ‘rewards’ are defined solely in terms of their ability to increase the probability of some desired and specified behaviour recurring. Similarly ‘punishment’ is defined solely in terms of its ability to reduce the probability of undesired behaviour recurring. It follows, that what counts as a reward for some individuals might count as punishment for others.

The research evidence on the efficacy of behaviourally dominated, that is, reward-punishment, management regimes points to several facts:

- punishment, in terms of withdrawal of privilege, is most effective when set in the context of a predominantly positively supportive social-emotional climate.

- providing children with external rewards for activities they are already highly interested in reduces the quality of their work and eventual loss of interest in those activities. Rewarding children for being on task in low interest activities does increase the quantity but not necessarily the quality of their work.

- shifting from a continuous to an intermittent schedule from tangible (physical) to token (social) and from extrinsic to intrinsic provides the best ‘rewarding’ structure for education success and personal development.

The alternative to a behaviourally oriented reward-punishment regime is to make use of the notion of intrinsic reward: the sense of self-reward that comes from satisfying one’s curiosity or puzzlement on the one hand or resolving one’s dilemma or problem on the other.

Rules Of Instruction Or Are They?

The roots of the “Keep-it-simple, stupid!” instructional policy are found in simplistic behaviourism. An instructive example comes from Ivor Davies’ Rules for Instruction in The Management of Learning. These rules embody the intuition that almost anyone could learn anything if only tasks were presented according to the five principles:

| Proceed | |

|---|---|

| From | To |

| Simple | Complex |

| Observation | Reasoning |

| Concrete | Abstract |

| Known | Unknown |

| Whole View | Detail and back to Whole View |

Few of these ‘rules’ stand up to pedagogic scrutiny. Why? Well consider; what is simple to one person (expert) is complex to another (novice), what we observe is already predetermined by our world-view bias, what can be treated as concrete by one person can treated as abstract by another. Even ‘moving from the known to the unknown’ is difficult to apply in practice, since how do we know what is known by the novice?

Only the last rule is in tune with Descartes’ common-sense, since it invites novices to start by sketching their whole picture, incomplete though it will be. This initial sketch, can be considered the novice’s initial whole view (what Ausubel called set of ‘advanced organisers’): it will inevitably be riddled with holes. The expert collaborator will be able to help novices help themselves sensibly fill the holes.

Self-Efficacy

Self efficacy is that sense of sharing in the control of one’s own actions: it is to be contrasted with learned helplessness. Self-efficacy in one subject area does not, necessarily imply self-efficacy in another.

Pedagogues are however able to adapt learning-to-learn principles such that they engender in their novices a growing self-belief in their ability to become expert in an increasingly wide ‘knowledge’ domain. The key to their success is their problem-formulating and solving rather than discipline-based approach.

Strategic Objectives

It is a commonplace to dichotomise between means and ends, process and product or strategy and objective. However this is an obstacle to effective pedagogic practice. These differences are reflected in the difference between being problem-driven or discipline-based. The relationship between the two aspects can be charted thus:

| Agreement on | Strategy | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Objectives | Yes | common purpose common methods | common purpose different methods |

| No | common methods different purposes | different methods different purposes | |

Task Analysis vs Ability Training

The most immediate challenge facing professional educators, is purportedly that of teaching learners en masse while simultaneously meeting the needs of the individuals comprising that mass. Given this view of ‘education’ it is not surprising that some individuals fail to achieve the intended targets. One of the few Golden Rules then applies: if we’re not getting the result we desire we need to change what we’re doing. But here the world-views of the policy designers determines which path is taken.

Psychologists of an atomist persuasion seek refuge in identifying and then reifying learning difficulties into learning dys-abilities. In addition, having identified ability differences they then prescribe ability training programmes, eg improve concentration, effort, memory, eye-hand co-ordination.

Pedagogues, by contrast, analyse and re-analyse the task and if necessary re-structure it to ensure novices eventually achieve task mastery. Re-structuring tasks entails, to use Papert’s approach , debugging the learners difficulties. This cannot be achieved by consulting norms or by applying theory generated in the laboratory.

Unit Of Discourse

Psychology has focused on and continues to focus on the individual and their processing abilities, whether in terms of difference or deficit. Pedagogy has accepted that we all influence each other both directly and indirectly, in intended and unintended ways, and for better or for worse. The pedagogic ‘unit of analysis’ or ‘universe of discourse’ is thus larger than simply individuals themselves, the elements are novice, expert and the material to be mastered.

To frame the problem another way, the whole of an individual’s problem is greater than solely the whole of that individual.